Kohukohu and the area

According to Te Tai Tokerau tradition, Kupe, the legendary Polynesian navigator and explorer, settled in Hokianga in approximately 925 AD, after his journey of discovery from Hawaiiki aboard the waka (canoe) named Matahorua. When he left Hokianga he declared that this would be the place of his return and left several things behind including the bailer of his canoe. Later, Kupe's grandson Nukutawhiti returned from Hawaiiki to settle in Hokianga.

According to Te Tai Tokerau tradition, Kupe, the legendary Polynesian navigator and explorer, settled in Hokianga in approximately 925 AD, after his journey of discovery from Hawaiiki aboard the waka (canoe) named Matahorua. When he left Hokianga he declared that this would be the place of his return and left several things behind including the bailer of his canoe. Later, Kupe's grandson Nukutawhiti returned from Hawaiiki to settle in Hokianga.

In the 14th century, the great chief Puhi landed just south of the Bay of Islands. The tribe of Puhi, Ngapuhi, slowly extended westwards to reach the west coast and colonise both sides of Hokianga. Hokianga is considered to be one of the oldest settlements for the Māori, and is still a heartland for the people. Rahiri, the 17th century founder of the Ngapuhi iwi, was born at Whiria pa to the south of the harbour, where a monument stands to his memory.

In this process of expansion the Ngapuhi created and maintained over centuries a complex network of walking tracks, many of which evolved into today's roads. Wesleyan and later Anglican missionaries were guided along these ancient routes to make their own discovery of Hokianga and its accessible timber resources. Their reports soon reached merchant captains in the Bay of Islands.

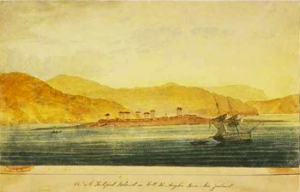

Captain Herd of the Providence was the first to respond, and with disgraced missionary Thomas Kendall as guide and translator, crossed the bar and entered the harbour in 1822 (the first European ship to do so) and sailed away with the first Hokianga timber shipment. His success inspired a strong following—the deforestation of Hokianga had begun and would be completed by the turn of the century.

The only disincentive to Hokianga's exploitation was the harbour bar. Of the hundreds of ships that successfully negotiated it, the records show that 16 were lost. Most came to grief when leaving fully laden and became caught in the wind shadow cast by South Head where the deep water lay. A temporary lull or change in wind direction could cause a sailing-ship to lose steerage way and be swept onto the rocky shore. In 1828 the missionary schooner Herald, built by Henry Williams and sailed by Gilbert Mair foundered, while trying to enter Hokianga Harbour. The last recorded shipwreck was the schooner Isabella de Fraine which was lost with all eight crew in July 1928 after capsizing on the bar at the entrance to the harbour.

In 1837 a French aristocrat with delusions of grandeur, Baron Charles de Thierry, sailed with 60 settlers into this hive of export activity to claim an immense tract of land that he believed he had purchased for 36 axes, 15 years earlier. He was eventually granted about 1,000 acres (4 km²) at Rangiahua where he set up his colony declaring himself 'Sovereign Chief of New Zealand', a title that failed to endear him to Ngapuhi. His project collapsed and he left behind him a few ancient fruit trees and a lot of gouty DNA. His visit at least inspired the Colonial Service to get on with a treaty in the face of this implied Gallic threat.

The year after de Thierry arrived another French connection, Bishop Jean Baptiste Pompallier, sailed in to establish a Catholic mission. He found the southern shores firmly in the hands of Methodist and Anglican missionaries, but the northern side was ripe for conversion. His remains, recently claimed by Ngapuhi, lie buried where the mission began. Today the harbour, like the Reformation, stands between Protestant and Catholic.

Within six days of the Waitangi signing, Governor Hobson, keen to secure full Ngapuhi support, trekked across to the Mangungu Mission House near Horeke where 3000 were waiting. This was the second signing of the Treaty of Waitangi on 12 February 1840. With the appropriate signatures (and a few inappropriate entries) he could immediately claim support from the biggest tribe in the country.

While the fate of the nation was being signed into history, the axemen of Hokianga scarcely missed a beat. At any one time, as many as 20 ships could be loading Hokianga timber. Whole hillsides, suddenly bared of vegetation, began to slip into the harbour choking its tributaries with mud.

The relationship between Māori and Pākehā (European) settlers was frequently tense, never more so than during the Dog Tax War of the 1890s, which was largely centred around Hokianga.

Information from Wikipedia

Within six days of the Waitangi signing, Governor Hobson, keen to secure full Ngapuhi support, trekked across to the Mangungu Mission House near Horeke where 3000 were waiting. This was the second signing of the Treaty of Waitangi on 12 February 1840. With the appropriate signatures (and a few inappropriate entries) he could immediately claim support from the biggest tribe in the country.

While the fate of the nation was being signed into history, the axemen of Hokianga scarcely missed a beat. At any one time, as many as 20 ships could be loading Hokianga timber. Whole hillsides, suddenly bared of vegetation, began to slip into the harbour choking its tributaries with mud.

The relationship between Māori and Pākehā (European) settlers was frequently tense, never more so than during the Dog Tax War of the 1890s, which was largely centred around Hokianga.

By 1900, the bulk of the forest had sailed over the bar and the little topsoil that remained was turned to dairy farming for butter production.

Source: Wikipedia